Ukranians Can’t Win

Opposition leader Pierre Poilievre called the Hunka affair “the biggest single diplomatic embarrassment in Canadian history.” I’m not sure if he’s correct, or even what he means exactly, but Putin was gleefully able to use the affair to argue that there seem to be a lot of Nazis in Canada, and that maybe, if Canadians hate Nazis so much, they should do something about it, as he is doing in Ukraine.

Jewish organizations, like B’nai Brith, agree with Putin on this, demanding the release of the complete Deschênes Commission Report (1986) into war criminals in Canada, so that they can determine exactly how many Nazis made it to Canada after WW II, how thoroughly they were investigated for war crimes, and why officials admitted them in the first place. Likely the purpose would be mostly educative, since almost all candidates for investigation are long dead, but some live ones could be tagged for extradition, as Jaroslav Hunka has been by Poland.

Jewish groups like to hold Canada’s feet to the fire over its tendency to protect and even honour people who might be or have been Nazis. The most famous case of this, immediately previous to Hunka, is that of Peter Savaryn, who fought in the same unit as Hunka. Savaryn was honored for his contributions to Canada and the Alberta Conservative party with a Chancellorship at the University of Alberta (1982 – 1986), and an Order of Canada (1987). He died in 2017, his honours intact, but when the Hunka affair blew up he came under the scrutiny of the Simon Weisenthal Centre. The Governor General who’d given him the Order of Canada apologized to Canadians, and the university began stripping him of his honours.

Communists would also agree with Putin. Deschênes reported that, soon after the war, as the Cold War heated up, Canadian politicians and immigration officials were far more worried about admitting communists to Canada than Nazis. Also, anti-communism almost always, as a cause, includes some good feeling for and cooperation with fascists and Nazis, from Klaus Barbie to Augusto Pinochet, on the dangerous grounds that, as the old saying goes, “the enemy of my enemy is my friend.” Maybe the (over-eager?) expansion of NATO to the Russian border, and the eagerness with which NATO countries are delivering arms to the Ukraine, is a sort of half-life anti-communism blind to the presence of Naziism in the countries NATO is trying to protect. Maybe NATO is half in love with the idea of the Ukrainians fighting a possibly endless proxy war against the Russia, thus draining Russia of resources and manpower.

As a matter of politics more than diplomacy, the Hunka affair could enable some Ukrainian and Russian Canadians to argue that, yes, Ukraine has always been suspiciously fond of its brief (1941 – 1945) Nazi past, which in most areas was a nightmare as bad as that inflicted by Stalin (1917 – 1941). For Ukrainian Jews, it was far, far worse. Some Russian Canadians might also argue that thinking of Ukraine as a democracy to be protected, and Russia a dictatorship to be fought, is an over-simplification.

I imagine that most members of Parliament would have twigged to at least some of these political-diplomatic implications of honouring Hunka, and felt the urge to run out of the chamber when the Speaker introduced him as a patriotic hero. They surely, after a couple of years of debates on Ukraine, would have known that, if Hunka was fighting Russians in 1943 – 1945, he had to be fighting with the Germans. Some of the parliamentarians, Chrystia Freeland for example, whose grandfather ran a pro-Nazi newspaper in Ukraine during the war, might have been thinking, uh, oh. But it’s obvious that MPs like Freeland were caught by surprise and, since Zelensky was there as an honoured guest, decided to keep their fingers crossed and go along with the Speaker’s show.

As for Zelensky himself, he must’ve been amused by the aftershocks. As a Jew, he wouldn’t have any love for Nazis but, as a Ukrainian, he would have known that men like Hunka are still honoured as freedom fighters in his country and that members of the Waffen SS receive veteran’s benefits. These things are subject to controversy in Ukraine, but have considerable public support. It’s unlikely Zelensky would take the affair as a diplomatic slight, and more likely that he would have shrugged it off as a misguided attempt to honour him.

The term “Nazi” is used loosely now, but it’s unlikely Hunka himself could fairly be defined as a one. Fighting in or with the Hitler’s army is no indication you’re a Nazi. Italian and Spanish fascists and Finnish patriots fought alongside Hitler. If being a Nazi means being a member of a Nazi party, Hunka almost certainly wasn’t one. It’s not likely that a Nazi party formed in Stalin’s Ukraine, so that Hunka could join up. Hitler’s Nazi party certainly didn’t admit Slavs, who were slated for eventual (once they were no longer useful as slaves) extermination.

If being a Nazi is defined more generally as adhering to a Nazi or neo-Nazi ideology, Hunka could be one, along with thousands in Canada and millions all over the world. Naziism implies extreme nationalism, military expansionism, and ethnic, sexual, mental and physical “purity” — which meant for Hitler, eliminating Jews, Roma, the mentally and physically disabled, homosexuals and Slavs. Most neo-Nazi groups choose selectively from this menu, but I could find no evidence that Hunka was any more than a zealous Ukrainian patriot.

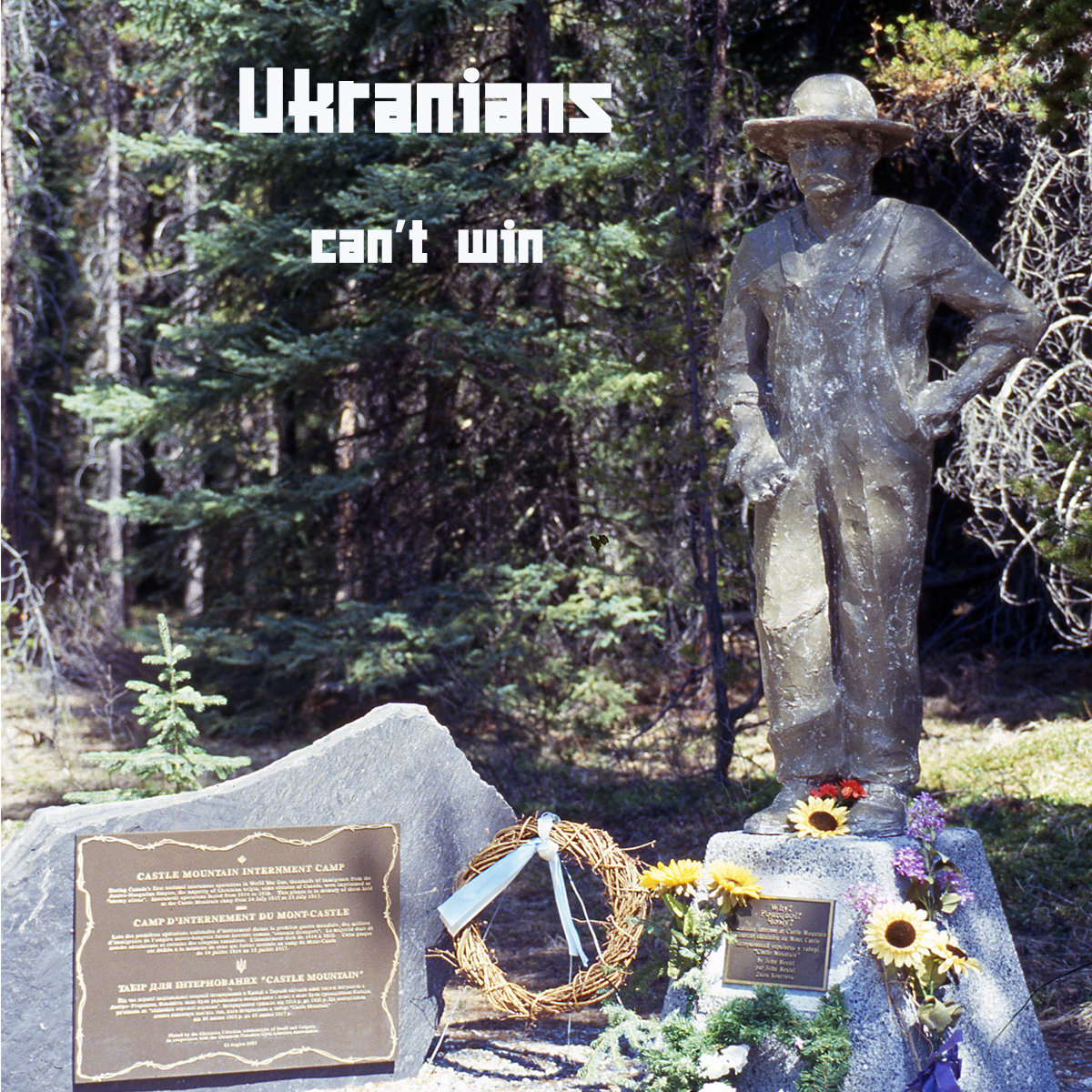

As such, he would’ve joined the Waffen SS because it was the only game in town when it came to kicking out the Russians. For most Ukrainians at that moment, Stalin was the real enemy. In the 1930s, when Hunka was growing up, Stalin instituted a policy of Russification, which worked mainly by removing Ukrainians to far parts of the USSR and replacing them with Russians. Hunka has written about seeing, as a boy in school, friends, neighbours and teachers suddenly disappear. Stalin also applied his economic planning to agriculture, causing a famine in 1932 and 1933 that killed up to eight million people in the Soviet Union, over half of them Ukrainians. Hunka had reasons, at age 18, to be very angry at Russians.

The response of the Canadian government to the affair was to deny direct responsibility and to issue a general apology on behalf of Canada to Poland (which regards Ukrainian Waffen SS soldiers as war criminals), to Jews and to Zelensky who, as I said, wouldn’t likely have wanted an apology. Poland could be seriously investigating the possibility of extraditing Hunka. This would lead to diplomatic and political problems for Canada. In 2013, another Ukrainian Waffen SS volunteer, of higher rank than Hunka, Michael Karkoc, who’d come to the US after the war, came close to being extradited, but died before it could happen. The Polish extradition request caused a lot of controversy in the US, with some Americans pointing out that countries like Chile, Iraq, Vietnam, and Nicaragua could use the Karkoc case to demand the extradition of some American military personnel for doing what Karkoc was suspected of doing.

The Deschênes Report was a reasonable attempt to avoid creating such long-term problems. The report announces that its purpose was that of the Nuremburg trials — more a matter of “discouraging future generations than of meting out retribution to every guilty individual.” Because almost all Germans — certainly the armed forces — were thoroughly Nazified, and because the bureaucracy and armed forces do things along a chain of command, only what the Report called (quote marks included) “major” war criminals were brought to trial. They were ones that could be held responsible for establishing and implementing policies which led (1) “to the war,” (2) “to the abuse of civilian populations and prisoners of war,” and (3) “to the attempted systematic extermination or genocide of whole categories of people.”

Crimes in which military personnel were involved, against other militaries (like summary executions) and against civilian populations (like bombing, shelling and besieging and starving them) were excluded, since Allied forces committed similar crimes (like the fire-bombing of Dresden). Such crimes were an unfortunate result of what Deschênes refers to as “the exigencies of war.” No one wanted to set the stage for Germany (for example) to start extraditing Allied personnel and putting them on trial.

The Commission noted that its work was made easy because the government and the Supreme Court quickly, after the war, eased immigration restrictions on members of the Nazi party, German soldiers, and collaborators: “The Nazi prohibition was dropped in 1950, non-Germans conscripted into the Waffen SS after 1942 were exempted in 1951, as were, in 1953, Waffen SS German nationals under the age of 18 at the time of conscription, as well as ethnic Germans conscripted under duress.” In 1962, specific exclusions were removed altogether and “there remained only the loose catch-all exclusion of those ‘implicated in the taking of life or engaged in activities connected with forced labour and concentration camps.” The Commission was able to focus on finding any of these people.

The government never provided a definition of “collaborator,” making things even easier. The Commission noted that an immigration-applicant’s “membership in the various Nazi-organized police auxiliaries that had been raised among local populations and used to keep order, to round up and sometimes to execute those suspected of being Jews, partisans, etc., was not a specific reason for exclusion.” Applicants for entry were not asked about these things, so couldn’t be accused of omitting to mention them. The Commission concluded that the government wanted to concentrate the efforts and resources of its officials on communists: “they were more concerned about denying entry to Communists and communist sympathisers than to Baltic nationalists who had collaborated with the Nazis.”

In the case of the Hunka affair and the talk of Hunka as a Nazi, Parliament, the government and some media journalists are indulging in what historians call “the condescension of posterity.” This attitude, featuring an insistence on thinking of justice and virtue in the abstract rather than in situ, inevitably leads to hypocrisy. The present tendency to refer to attacks on civilians as “terrorism” (for example, Hamas “terrorists”) would apply to any situation where civilians are bombed from the air or shelled and attacked on the ground. During the American revolution, civilians were attacked by both sides, their property taken and their persons tortured, transported, or worse.

I think if anyone deserves an apology in this situation, it’s Hunka. It would have to be one limited to the incident of him being celebrated in Parliament only to be denigrated after by politicians as a war criminal. So far as anyone knows, he is innocent of war crimes, and doesn’t deserve to be tagged with the term “Nazi.”