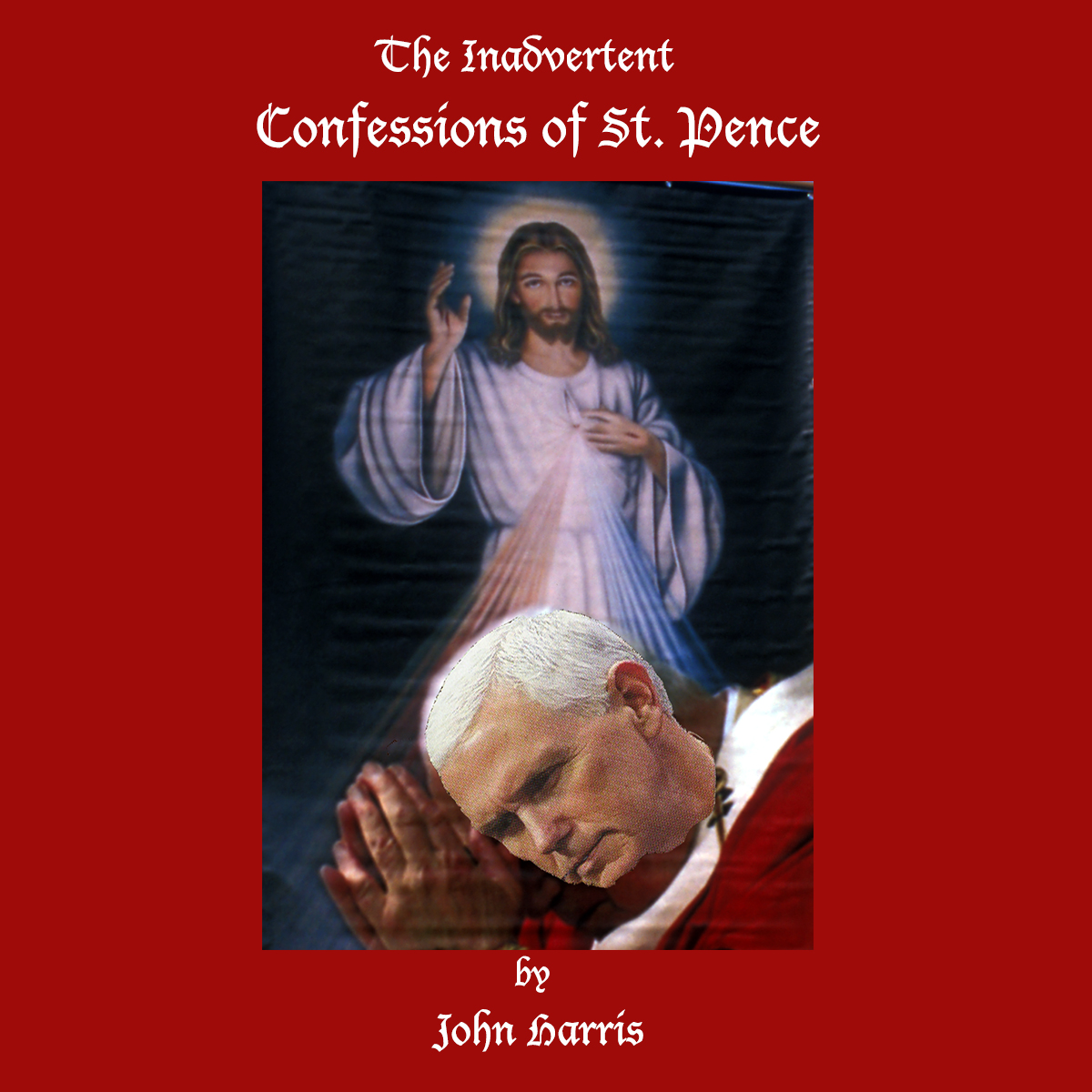

The Inadvertent Confessions of St. Pence

A Review of So Help Me God (Simon and Shuster, 2022)

By John Harris

Mike Pence is no thinker. So Help Me God is more interesting for its contradictions and lacunae than for what it says. It’s an emotive appeal to Pence’s base, a celebration of the profundity and efficacy of his religious and political values, a defense of his record as congressperson, governor of Indiana, and Donald Trump’s vice-president, and the opening shot, maybe, of his campaign for the Republican leadership.

Pence defines the art of governing as “finding realistic solutions within the framework of your principles.” Within that framework are the principles themselves (usually stated in the form of verses from the Bible, and sometimes by reference to sections of the Constitution), personal anecdotes that affirm those principles, and the opinions and personal anecdotes of those working within the same framework, most of them Republicans. References to polls, statistics and the opinions of a wide range of journalists, theologians, academic experts or other politicians are not important in determining what’s “realistic.”

This is abnormal, and it explains why Pence was blindsided so often. He was blindsided, as he says, by the Democrats taking the House in 2018, by Biden’s win in 2020 and, most famously, by Trump’s reaction to that win — his attempt to talk Pence out of certifying the election results. He was blindsided, more significantly, by his failure as governor to pass his Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA), meant to protect traditional marriage in Indiana. The Act was opposed by moderate Republicans, the business community, and the media. Pence was forced to amend his bill to prohibit discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity, even though he was convinced these amendments would limit the religious freedoms of his Hoosiers (Indianans).

Most significantly, Pence was blindsided in 2016 by his running mate Trump’s message to the multitudes, realizing for the first time that Hoosiers “felt firsthand what the US elite barely realized: wages weren’t keeping up with inflation, entire communities were being hollowed out as factories closed and moved to Mexico or Asia. What they saw from Washington was contempt and constant reminders that their country was just one of many, no better than any other and probably worse. And they had lived with the fall-out from a long series of policy choices — from trade pacts to unending foreign wars.”

Pence, by that time well established among the Washington elite, doesn’t explain or apologize for most of his political miscues or policy failures, but he does show regret for not seeing earlier what Trump saw: “I had supported free trade and the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq.” It is honest of him to point this out, but doing so puts paid to his attempt to justify his method for finding “realistic solutions.” And he still stands by his votes for the trade deals and the two wars. The fact is, Pence is a crusader more than a politician, and once the crusade starts it becomes its own justification.

In his defense of his own RFRA, he sounds like a hurt child, crying about being ganged up on by everyone including his friends. Opponents of the bill were unfair in that they didn’t make their objections known until he signed it. After he signed it, “All hell broke loose . . . . Angry statements were issued by corporations. The woke brigades of politicians, media, and corporate America mobilized before wokeism was even a thing. The progressive Left and its allies in the media began by grossly mischaracterizing the bill as a ‘license to discriminate’ . . . . The overwhelming opposition we faced from the Left, the media, and corporate boardrooms had all the markings of a coordinated effort.”

This sounds like paranoia. He does admit doing stupid things in connection with the bill, like signing it in private with a bunch of religious leaders, and losing his temper at insinuations that all Hoosiers might not see the line between protecting traditional marriage and protecting heterosexuality. He also argued that, as a Hoosier, he and his family would never discriminate against anyone, and that a Hoosier baker, having the right to refuse producing a wedding cake for a Hoosier gay couple, would never assume they had the right to refuse to sell that couple bread. Pence seemed to forget what almost everyone else realized: that evangelicals object to homosexuality itself as a sin against God, and many Hoosiers would feel quite righteous in refusing gay people services of any sort. He also tried to twist on what the bill was about, not so much religious freedom but expanding government: “The law was not about discrimination, it was about fighting government overreach.”

Pence has a tendency to reconcile what many might consider opposing principles by prioritizing them. He is “a Christian, a Conservative and a Republican in that order.” A version of this is his description of his duties as VP — “to God, the Constitution, and the President” in that order. God was left out of the Constitution for a reason: no one can agree on what he wants, and fighting over His Word can introduce an element of fanaticism into politics, the lowly art of the possible. But the main point of So Help Me God, the topic of about 2/3 of the book, is to dispute this — to show, in terms of how he and Trump got along and did great things, that his three identities, his prioritized sets of duties, fit together.

The book starts with the story of how Pence arrived at his values. He describes a happy upbringing with prosperous, loving parents and siblings in a community (Columbus, Indiana) that is friendly and compatible even though his parents weren’t born there and were in a minority as Catholics. He focusses on how he acquired the principles that guided his political life. These, he says, were the values of Hoosiers, who are patriotic (defending their ideals in the Mexican-American War and Civil War), and “tough, independent, hard-working, creative, and caring. They value faith and family.” These values are, as Pence has it, also America’s, his parents’ and his.

This sounds familiar — the sort of family and civic boosterism that politicians are prone to when they’re building and appealing to a base. And, sure enough, boosterism is what it is. Pence admits that, in high school, despite all the sturdy community-and-parental value-reinforcement that he got, “I wasn’t sure where to turn or who I was.”

Since Pence declines, out of embarrassment perhaps, to describe any behavioral problems that would normally have come from such a state of angst, the reader is left to guess what happened. The best guess, probably, is that his parents and community instigated what psychologists call “identity foreclosure,” by forcing an identity on young Pence instead of allowing him to arrive, on his own terms, at “identity achievement.” This would not have been their fault. Pence was a malleable young lad, easy to get along with and a bit lazy in high school, but in need of certainty. Obviously, he’s a Christian because everyone around him is a Christian, and he’s an American because he was born in America, but Pence sees these identities as conscious choices, which means that anyone who isn’t Christian and American is flawed

If Hoosiers make up an intimidating phalanx of upright folk, his father, as Pence describes him, seems a positively monolithic paragon of rectitude. If young Pence were in search of an identity, he wouldn’t want to show it. Dad ran the family as if it were a platoon, Pence says. He was a “nominal” Republican, a second-lieutenant who earned a bronze star in Korea, a business executive with a college degree who was part owner of the company he worked for, a golfer, and a member of St Vincent de Paul. He insisted that all his kids do college, and that they work at jobs to pay their way. He dished out a kind of tough-love, cryptic wisdom, often accompanied by the locking of eyes and the wrying of smiles. One time, Pence asks dad why he was parsimonious when it came to words of encouragement but generous in his criticism. Dad says, “The whole world is going to tell you how great you are. My job is to tell you how to do better.”

Another Ancient Mariner moment occurs when Pence, a bit overweight, an average student not good at sports, tells his father about winning one of the local American Legion’s oratorical contests — speeches on the topic of the US Constitution. Pence produces a fistful of blue ribbons, saying proudly that he won them without even putting in much work. Dad says, “All I ever want to know is if you did your best, not if you won or lost. I don’t have any use for these ribbons.”

Pence heads for Hanover College in September 1977. It’s there that his three identities are quickly, maybe too quickly, infused with tapioca. He attends nondenominational chapel services, mainly to meet girls. He meets, instead of girls, some upperclassmen from his fraternity, who party vehemently but also talk much about their personal relationship with God. In the summer of 1978, he travels with some of these friends to the Ichtus festival, “the Christian answer to Woodstock.” There, moved by the music of the Pat Terry Group and Andrus, Blackwood and Co, and (mainly) by the preaching, he answers the altar call and is born again. He finds Wisdom, or the source of same, at 19 years of age.

As Pence explains it, his revelation happened “not because I was convinced in my mind of the truth of the Gospel but because my heart was broken with gratitude for what had been done for me on the Cross.” It was Christ’s sacrifice, in other words, to redeem Pence and give him a chance at Heaven, more than Christ’s words, that won Pence over. The Gospel itself, as Pence has it, the words and the story of Christ, is not enough.

At first Pence continued to attend Catholic services and some non-denominational ones. He defined himself as a “born-again evangelical Catholic.” In the mid-nineties, he joined Grace Evangelical Church in Indianapolis. But, since then, he has said that he is still looking for a church. Nothing quite fits. Likely, he feels he doesn’t need one.

Pence is given to prayer when faced with serious personal and political decisions (Trump remarks about this, “That’s not exactly how we start real estate meetings in New York”). He leads a prayer in the Situation Room, for example, when US Special Forces are going after Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the “theocratic sadist” who led ISIS. Pence prayed “for the safety and success of the mission and for justice to be served” — for the soldiers to live and for Baghdadi to die, in other words. He prays with his Coronavirus Task Force when they start planning their campaign. He also keeps his eye out for “providential signs.” For example, he realizes that Providence has put him beside Trump when the decision is made, against the advice of Rex Tillerson, General Mattis and foreign leaders like Emmanuel Macron, to move the US embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem, thus recognizing the city as the capital of Israel, and righting the wrong committed by the Romans in the second century AD.

Pence refers regularly to the Bible for advice; every chapter in the book starts with a piece of scripture, Pence’s interpretation of which guides him through the personal or political problems he faces in that chapter. Some of Pence’s examples of Biblical exegesis are hard to connect, and some are ridiculous. At the time of Trump’s inauguration, Pastor Robert Jefferies gives an “inspiring” sermon on how “God loves walls.” Jefferies compares the wall Nehemiah had built around Jerusalem to Trump’s wall along the Mexican border. The trouble is, Pence has earlier told the story of how he and his brother Gregory, on a European walkabout, pass through Checkpoint Charlie on the Berlin Wall from west to east, from “freedom to tyranny.” Was that wall, the one that Reagan advised Gorbachev to tear down, also loved by God?

In the case of abortion, the issue on which Pence claims (with good reason) to have achieved resounding success, Biblical guidance came early, not from Catholicism but from the day when Pence found Jesus: “When I opened his Word, I read, ‘before I found you in the womb I knew you, before you were born I set you apart,” and “I have set before you life and death, blessings and curses. Now choose life, so that you and your children may live’.”

These passages are from Jeremiah 1:5 and Deuteronomy 30:19 respectively, and you’d have to be born-again to see how they apply to abortion. Calvinists see the first as talking about election, the list of those predestined go to Heaven. The Elect are predestined, according to Calvin, not from the moment of conception, but from the beginning of time. It might be thought, too, by the layperson, that because these passages are from the Old Testament, they cannot be the words of Jesus. It seems that born-again Christians read the entire Bible as the word of Jesus in the sense of “like Father, like Son.”

On the abortion issue, Pence’s born-again Republican heroes, Ronald Reagan and George W. Bush, had the right idea but not the grit. Reagan had misgivings about his California law that permitted abortion in cases of rape, incest, and the risk of a mother dying. But, as President, he let a law like this stand and didn’t see to it that all of his Supreme Court nominations were pro-life. George W. Bush’s No Child Left Behind Act permitted stem-cells to be extracted from fetuses that had already been harvested, so Pence, the crusader, couldn’t vote for it. “I am and remain a supporter of research on adult stem cells, but never embryonic ones.”

As Governor of Indiana, Pence signed a law that criminalized abortions based on race, gender or disability. There’s no record of women getting (or admitting to getting) abortions for the first two reasons but, as Pence says, “in the US and elsewhere, the vast majority of babies diagnosed with downs syndrome are aborted.” Pence, and his wife, don’t understand this: “Karen and I had spent time with families with Down syndrome children on charity walks and picnics . . . and had always been moved by the parents’ devotion to the child and the boundless joy of those special needs kids.”

Pence’s solution to unwanted babies is adoption, which he and his wife were at one time (while they were trying to have kids of their own) about to do, putting their money where their mouths were, so to speak. They were at the top of the list of desirable parents, but decided to let the second-choice couple take the baby as that couple was infertile. However, since there are thousands of babies and children looking for adoptive (or foster) parents, more than can ever be provided with parents, it’s strange that the Pence and his wife didn’t try again, even though they had their own kids. It’s also strange, since down’s syndrome children are almost impossible to find parents for, that Pence and his wife didn’t take one of them.

Pence’s conservative and Republican identities firm up at college, just as his Christian one does. Pence is at first a Democrat (his mother’s influence), and an admirer of John F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King. He admires them as he admires Jesus, “for their “eloquence and tragedy,” not particularly for their words. However, one of his professors, in the second term of his freshman year, begins to turn Pence towards Republicanism. George M. Curtis III, another man given to dispensing tough-love wisdom, teaches him that the Constitution is more than an operating manual for the US government, which is how Pence had been describing it in his public-speaking exercises. As Pence summarizes Curtis’s lessons, “underpinning” the Constitution are “principles” that “allowed Americans to flourish and realize their dreams.” These principles are “fiscal discipline, freedom, and limited government,” the same principles espoused by the Republicans. When the Constitution is looked at from this perspective, says Pence, “the virtues of our constitutional system of limited government, the failings of socialism and the tyranny of Communist government came into high relief.”

Of course, there are no such principles behind the Constitution. The Constitution is a product of the Enlightenment, that worshipped “Reason.” Jefferson decorated the White House with busts of his intellectual heroes, Bacon, Locke and Newton. Pence is correct, for example, that Communism wouldn’t fit, as one-party rule. But socialism, as democratic socialism, does. Under the Constitution, Congress is free to do socialistic things: set taxes as high as it wants, seize ownership (so long as owners are compensated), provide welfare and social services, and run large enterprises. Also, Pence seems to see social democratic countries as successful. When he and his brother go through Checkpoint Charlie, they pass through social democracy in the form of West Germany, and find it sweet, with “glittering lights, bustling traffic and crowded restaurants and shops.”

It takes a few years for Curtis to swing Pence. He votes Carter in 1980 but, due to Curtis, he is actually listening to Reagan and finding him to be spot-on. He does his senior essay under Curtis and, over the next couple of years, working as the college’s admission officer, continues his studies informally in Curtis’s residence. Curtis became more “candid” there, “and my own transformation from Kennedy Democrat to Reagan Republican neared its conclusion.”

Pence joins the Republican party (and the “Reagan Revolution”) in 1983, at age 24, when he is studying law at Indiana University. While studying, he works hard for the party, marries (becoming his wife Karen’s second husband) and graduates in 1986. In 1987, the party asks him to run for Congress, and in 1988 he wins the nomination. But his entry into politics is, for a few years, a disaster. This is mostly, he says, because he is over-ambitious. Really, the word would be over-zealous. He gets to meet Reagan, at the end of his presidency, who blushes at Pence’s outburst: “I just want to thank you for everything you’ve done to inspire my generation of Americans to believe in this country again.” Other prominent Republicans try to warn him that he’s too eager to win. He loses, but runs again two years later. Again, he ignores warnings that his ambition is too visible. Desperate to win, he adopts a “pugilistic” approach in his speeches and advertising. He offends voters and is soundly and, he affirms, deservedly defeated. He vows never to abandon his principles again.

He lands a job leading IPR, a conservative think tank. Quite by chance, it’s there that his conservatism takes its final form. He brings in theorist Russell Kirk, famous among conservatives for The Conservative Mind: From Burke to Eliot (1953), He asks Kirk “are you a conservative, a neo-conservative, a libertarian? Which is it?” Kirk says he’s a conservative. Pence, eager to resolve the issue of his second-most-important identity, repeats his question, so Kirk sends him his book, The Politics of Prudence (1993), as an answer.

This book becomes a lifelong inspiration— Pence studies it “on most vacations” — but what he got from it is a mystery. In describing his reading of So Help Me God, Pence focuses on a single anecdote about how T. S. Eliot, “poor and overworked,” had stepped out and founded a magazine.” He seems to see Eliot primarily as a good example of entrepreneurial get-up-and-go. This is beyond odd. There are far more important features of Eliot’s conservatism that Kirk describes. First, Eliot was a Monarchist and so an Anglican, the Christian denomination of which the monarch is the head. Second, Eliot liked classical Greek and Roman democracies, (parliaments of oligarchs governing slave societies), not modern democracies, and especially not American democracy. Third, Eliot, was a racist. He didn’t think any country (like America) with a significant population of free-thinking Jews could be functional, and he thought black people were sub-human. Third, he liked Mussolini, especially his policy of shooting socialists.

Kirk’s book, however, did answer Pence’s question about types of conservatism. Here again, it is hard to ascertain if Pence heard the answer. Kirk told him that Libertarians, a sort of rump of the Republican party at present, are merely “chirping sectarians.” They share with conservatives an opposition to the totalist state, but are forever, like Calvinists or Marxists in search of ideological purity, splitting into smaller and odder sects, rendering them disruptive and politically ineffective. Kirk’s book also told Pence that neoconservatives, the great contemporary example of which is George W. Bush, are nationalistic fanatics who are infatuated with ideology over common sense and dream of creating, through “democratic capitalism,” a “great society.” Promoting this idea of the perfectibility of mankind, they ignore, as liberals do with their faith in progress, the lessons of history. Neoconservatives believe that the Constitution can be exported by means of military conquest. Finally, they believe, along with neoliberals, that liberal democracy and capitalism can be introduced into theocratic, fascist, or communist societies through free trade.

Pence’s conservative ideology features some of the libertarian principles (primacy of the individual conscience and opposition to big government), and lot of the neoconservative ones (militarism, American exceptionalism, and faith in free-market capitalism). Pence does object to the American military being involved “nation building” in Afghanistan, but accepts it because it is necessary to selling the public on a continued military presence there, something he advised Trump to maintain.

Kirk, like his hero Edmund Burke, was against idealism of any sort having a place in politics, and would have seen Pence’s emphasis on Christian values as a blight on his attempt to find realistic solutions to political problems. Eliot’s Christianity, as Kirk explains — the Anglican or Episcopal sort of Christianity — fits with conservatism because it appeals to tradition. The Monarch, and the church, handle the interpretation of the Bible and the expression of principles. Liberals, who believe in “liberty, fraternity and equality,” and aspire to the perfectibility of the individual and of the nation, can, as progressives, become Pence’s equals in the extent of their idealism and the futility of their politics.

The trouble, as both Burke and Kirk saw it, is that no individual fully agrees with any other individual’s principles, so you can’t base a political system of an appeal to a set of agreed-upon principles. The founding fathers took basic values to be “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.” These were “self-evident,” in the sense that they are vague enough that everyone could agree upon them. To protect individual life, liberty and happiness, the main threat to which comes from other people, you need rule-of-law. Faith in Pope, King or Country is the old-fashioned, unenlightened way to go. The US Constitution is a more sophisticated prosthetic to help members of a civil society walk upright.

What saves Pence as a politician is what he considers his major weakness: ambition. The desire to win power and keep it forces him to accept compromise, even while he vows to fight on. Pence’s book shows how this worked out during his time with Trump, and answers the big question that people have about Pence: how did he keep his principles intact in the service of someone who had none?

So how did he manage? Pence’s reason for his loyalty to Trump starts with the “Christian first” factor of his method. “Providence put President Trump behind that desk, and I was elected to serve as his Vice President. My job, my calling, was to help him be successful in the presidency he had been elected to advance. It was that simple.” In other words, Pence feels ordered by God to accept and advance Trump’s agenda, whether he agrees with it or not. Not only that, but he is ordained to defend Trump’s priorities and management style, even if they are different from his own priorities and style as reflected by his record as Governor — a style that, unlike Trump’s put “a premium on civility,” whereas Trump’s was “confrontational.”

Trump’s leadership style is defended by Pence, not as “Christian” but as “typically American” — pugnacious and upbeat. It is caffeinated Republicanism. He compares Trump to Andrew Jackson, “Old Hickory.” Trump, Pence claims, could speak directly to working men and women, “the secret of his success as a businessman.” “My dad had the same quality.” He also defends Trump’s style as business-like, corporate — a style he believes is more efficient than that of Obama, the Bush’s, or even his as a governor. For example, Trump’s “You’re fired!” approach to his bureaucracy led to efficiency: “If an employee isn’t getting the job done to the employer’s expectations, he or she usually has to find work elsewhere.” Also, Trump watched the budget as the Bush’s and Obama never did.

Next, Pence refers to the Constitution. Its guidance is more specific. It defines the VP as President of the Senate. His duty is to preside over its sessions, but he “shall have no Vote, unless they be equally divided.” Another duty is to certify the tally of electoral votes after an election. Finally, the VP has to stand in for the President when he gets sick, and replace him if he dies. However, over time, additional duties have accrued to the VP, and these less formal ones are the ones that attracted Pence. The Constitution doesn’t talk about the VP as supporting or advising the President or as being assigned specific “portfolios.” These roles are now expected — Pence sat on advisory committees and was responsible for the space program and government response to the Covid epidemic.

Pence sees Walter Mondale, Carter’s VP, as “the first modern Vice President.” Mondale was a member of the cabinet with an office in the West Wing, and he performed important diplomatic functions like preparing the way for the Camp David Accords between Israel and Egypt. Pence sees himself as Trump’s best and most trustworthy advisor, a view confirmed by Newt Gingrich and Tony Fabrizio, a Trump pollster. Trump probably did appreciate Pence’s loyalty and invite his participation in committee meetings as Pence says he did; Pence was the one person in the White House who couldn’t be fired, so it would be awkward to face resistance from him in committee meetings.

Pence provides a detailed and rather vivid description of how he served. He starts by describing a typical day in Washington. He gets up and reads a reminder he’d written with a black felt pen on the bathroom mirror: “Be informed. Be prepared. Be of Service.” Then he reads his presidential daily brief, the same overview of national security threats that Trump got. Then he reads four newspapers: the New York Times, the Washington Post, the Washington Times, and the Wall Street Journal, the four papers that Trump reads, focussing on “what’s above the fold.”

Then he reads Trump’s Twitter feed. Trump was the first president to use social media to stay in constant contact with the public. An equivalent might be FDR’s “fireside chats” during the depression and war, but that was only a one-way transaction. Trump assigned staff to read responses to his tweets and compile them into voter polls and prioritized suggestions for policy. Trump wanted responses; he always asked Pence, “did you see my tweet?” Pence didn’t often like Trump’s tweeting, particularly, when Trump summarily fired advisors (like Rex Tillerson, who Pence liked for his thoroughness and honesty), by tweet. He did appreciate how Trump used tweets to manipulate media, though — mainly to distract media attention from what he was really doing.

The first order of the day, once Pence got to the White House, was the PDB conducted by the director of the CIA with some of his staff, and the national security officer. Pence contributed to the meeting only by asking questions on Trump’s behalf. He did so because he knew what Trump’s “particular interests” were, and he always avoided seeming pretentious by asking Trump’s permission. The rationale about “particular interests” is probably evasive. Trump, as many of his executives learned, had a short attention span, and never read his briefs, and Pence was likely just trying to keep him on course when it came to Pence’s own interests.

After that, there were meetings conducted, usually, in the Oval Office — the ones to which the president’s assistant summoned him. These meetings would concern “everything from tax cuts and trade to building a wall on the southern border,” and Pence implies he was in on most of them. “I never just walked in,” he says, “I always waited for the president to invite me in.” In this, he was following Luke 14:10-11, where Jesus advises, “When you are invited, take the lowest place, so that when your host comes, he will say to you, “Friend, move to a better place.” Pence doesn’t say that he was invited to all of the meetings, but implies he was at the important ones.

Pence’s place was usually to the immediate right of Trump. At these meetings, once again, Pence intruded only to ask questions on the president’s behalf. Occasionally, Trump would ask him for an opinion, but Pence always said “Let’s talk about that later.” That talk was always in private and “Yes, I always had my own opinions, and, no they were not always the same as the president’s.”

This latter claim is honest. On foreign policy, for example, the book shows that Pence was much more hawkish than Trump. Trump wanted to talk to Kim Jong-un; Pence advised against. Trump wanted to merely threaten cancelling the Iran deal (signed by all the members of the UN Security Council) to see if the deal could be improved. Pence, convinced, as were the leaders of Israel, that the Iranians were cheating, wanted out. Trump wanted to invite Taliban leaders to Camp David to discuss an arrangement by which the Americans would leave and they would take over the country; Pence said no, “these people are animals.”

Trump’s administration was known to be tumultuous. Bob Woodward has described it as a circus, Trump’s officials and advisors working as hard to subvert his policy ideas as facilitate them. But Pence sees most of the better-known upheavals in the administration as being the fault of the Democrats (particularly Nancy Pelosi) and the Media (particularly the New York Times and NBC’s Rachel Maddow), who were forever trying to ambush Trump. Pence regarded the two attempts as impeachment and one whereby Congress would use the 25th amendment to remove Trump as unfit, as acts of grandstanding orchestrated by Pelosi.

The upheavals that Pence felt more personally concerned with were the firings and resignations of White House officials. For one thing, Pence had been involved in appointing them. For another, most concerned officials connected this with national security, perhaps Pence’s most important concern after abortion and Obamacare. Finally, the firings and resignations usually resulted, immediately, in “a scathing and self-vindicating tell-all book about the White House.” Pence implies that he has to defend himself in his own book.

The major controversial figures were Lieutenant General Michael Flynn (national security advisor), Lieutenant General H. R. McMaster (Flynn’s replacement), James Comey (Obama’s and then Trump’s choice as CIA Director), Rex Tillerson (Secretary of State), former senator Jeff Sessions (Attorney General), and John Bolton (McMaster’s replacement). In each case, Pence defends Trump’s choice, affirms his admiration of the person, and (except in the case of Bolton) justifies the firings and resignations as proper. Pence liked foreign policy hawks. He said publicly that he hoped to welcome Flynn back into the administration, and he was totally supportive of Bolton, as Bolton says in his own book.

Will So Help Me God help Pence advance to the American Presidency? As a crusader, Pence engages in politics as a mafia-style turf-war, Democrats against Republicans. He dislikes Libertarians because they break ranks and he uses populist arguments to win support. Polls show that most Americans are tiring of this.

As for his platform, the book also shows that, as President, he would be much more efficient than Trump in pursuing an agenda of tax cuts, pro-life Supreme Court appointees (his hero, Clarence Thomas, could be the next justice to go), a hawkish foreign policy (Bolton and other haters of the UN likely welcomed in defense and foreign affairs portfolios), and the elimination of “entitlements” — welfare without means tests — like Obamacare. On immigration and refugees, he would likely close the borders — he tried as a governor to force the federal government to admit no Syrian refugees. His daughter Audrey called him on this; she had visited the camps in Jordan. Pence says they had a “heated argument,” and had to “agree to disagree.” He was all in favor of Trump’s wall. In regard to Mexicans trying illegally to get into the US, he was in favor of separating kids from parents as a deterrence, though he seems to have appreciated Melania Trump’s intervention to end this policy and take the heat off the administration.

Economically, he would favour trade deals, but their objective would be more to freeze out China than improve the US economy. The deals would be attempts to buy allies, which could cost. He is a fiscal hawk, and voted against Bush’s program of buyouts and economic stimulus acts — a program that was administered by Obama. However, that program seems to have worked.

Socially, about mass shootings, Pence has always supported the existing gun laws and sees, not the guns themselves as the cause, but mental illness and “broken families, broken homes, and broken souls.” This “sickness across our land” can ultimately be solved only by prayer (2 Chronicles 7:14). To try to reduce the damage by improving license checks and limiting rifle capacity would be a violation of the Second Amendment. Meanwhile, building more mental hospitals and placing armed guards (retired police, preferably) at schools, could help as interim solutions.

Finally, So Help Me God indicates that Pence’s overall manner as President would be insufferably sanctimonious. He’s always very sure that he speaks for God. This makes him humorless, and ungracious in defeat.

Well, put, old son!