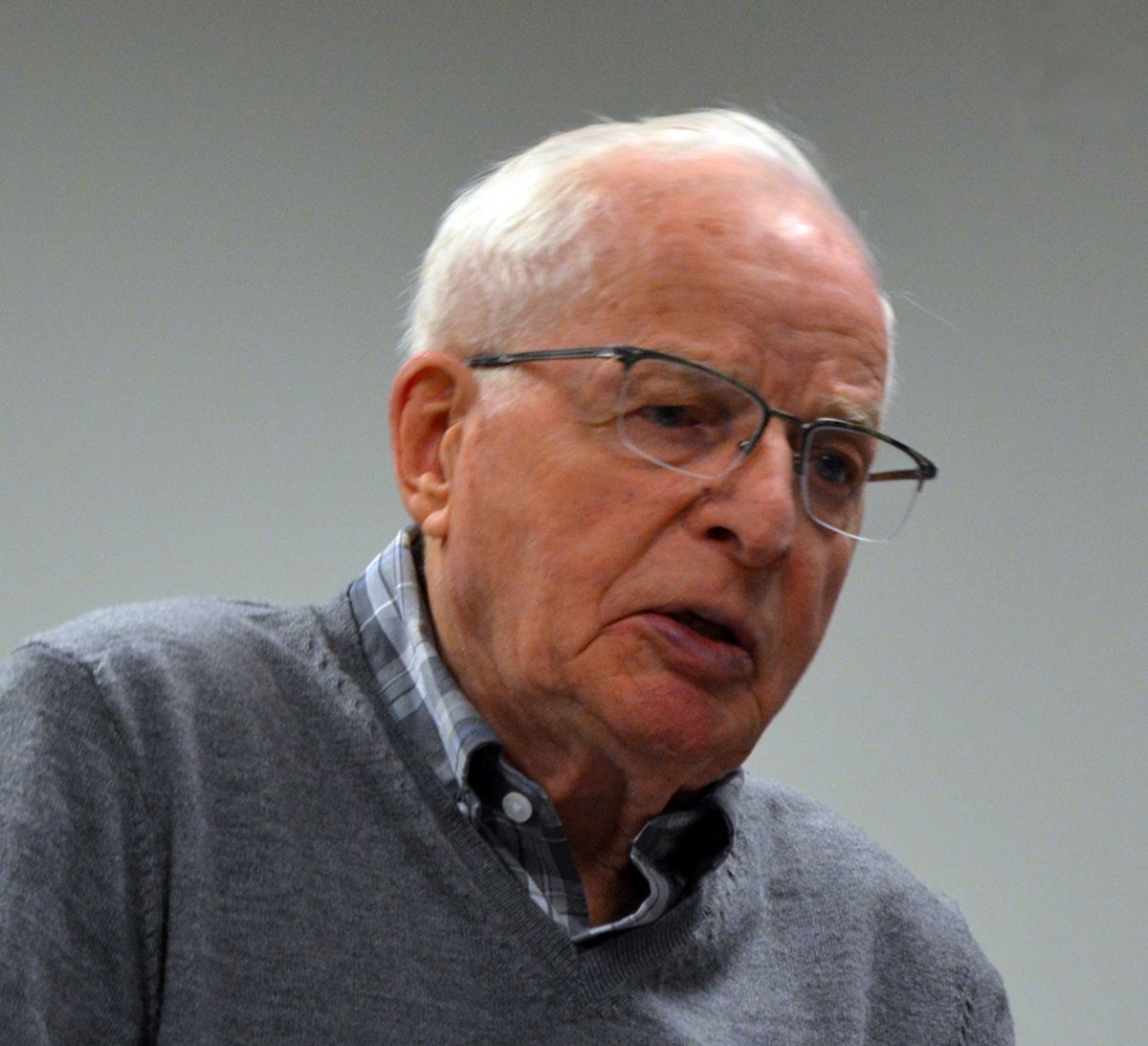

“The First Decade:” A Talk by CNC’s Second Principal, Fred Speckeen

Fred Speckeen’s talk, part of CNC’s 50th birthday celebration, was a personalized, humorous, and necessarily abbreviated account of some rather complex history. That history started about a decade before Speckeen turned up at CNC, with UBC President John B. Macdonald’s 1962 report on post-secondary education in BC, a report that recommended the establishment of two new universities (one in the Fraser Valley and one in Victoria) and a college system throughout the province.

Speckeen reflected on how no one at the time quite knew what was meant by a college system, because colleges in other provinces took various forms, some including all of the three instructional streams of CNC today (trades, technologies and university transfer), and some not. BC already had a vocational school system in place, and that system had expanded into Prince George in 1964. BC also had grade 13, as a more accessible passage for some students into second-year university. It didn’t exist in Prince George at the time, but there was considerable support across the province for expanding the grade 13 program as the least expensive way of improving access to university.

A year after Macdonald produced his report, in 1963, some school districts in northern BC decided that they wanted a two-year Community College, teaching university courses and technical programs like nursing and forestry, some of which fed into BCIT. To get a college, they had to establish a steering committee, they had to have a referendum in their areas about the proposal, and then they had to have a referendum on a funding by-law. Speckeen described how this played out in the north, which was not smoothly. He commended Doctor Mooney of Vanderhoof and Harold Moffat of Prince George for seeing the process through, calling them the “godfathers” of CNC.

He also mentioned that this committee chose to name the college after the name Simon Fraser gave the area — a name that came to be applied by the Hudson Bay Company to all of BC except for the colony of Vancouver Island. He wasn’t sure who specifically, had come up with the name.

The districts got the proposal through but lost on the funding. They had the right to move forward anyway, using their own money until they could win a funding by-law. They formed a college council, which hired, as the college’s founding principal, Wolfgang Franke, who had been president of Lambton College of Applied Arts and Technology in Sarnia. Speckeen didn’t say anything about Franke, which could be seen as a serious omission since his talk was called “The first Decade.” But the omission was possibly a matter of professional solidarity, because Franke’s tenure was a disaster.

Under Franke, the college, as a university-transfer and technical-program institution, started up in September 1969. There was a staff of 24 and a student body of about 260 (full and part-time). The College used the PGSS library, labs and classrooms (from 4 to 10 p.m.). Vanier Hall (with 800 seats) was used for literary readings, theatre events, and special lectures. Faculty and management offices were in a portable building (with, Speckeen noted, no washrooms) on PGSS grounds.

Speckeen was hired when it became evident that Franke was not able to manage. This was not entirely Franke’s fault. With university faculty and students came university life, which at that time included protest marches, visiting speakers with political messages, and a vibrant and heavily politicized student association and newspaper. The dominant issues at the time were the war in Vietnam, environmental pollution and acid rain, and the “New Left” efforts to democratize society from the bottom up. For students, the “bottom” meant their college.

The resulting mayhem (which drew in PGSS students too) shocked a community that, as indicated by the referenda, was not entirely sold on the idea of a university. Now it was starting to choke on the idea. The Council and other local politicians blamed this on Franke, and Franke was expected to tone things down. No one could have done this, but Franke didn’t seem to even want to. He felt that lively political controversy should be a factor of college life. Let them picket the settling ponds out at the pulp mill, and stop traffic on Central to draw attention to the Vietnam war. He thought it was good for them. Franke had also encouraged students to, as he put it, “participate in policy-making,” and he provided them with some of the means to do so.

Ian Johnston, Barry McKinnon, Gwynneth Evens, John Harris, Graham Dowden

The English Department

Speckeen, who’d been working as Vice-Principal of Cambridge College of Arts and Technology in Sudbury, was immediately a calming influence. He was familiar with campus agitation and the means that universities used to calm it — largely by formalizing student participation. He was lucky too. The US was making conciliatory moves concerning Vietnam at the time and, in 1971, a recession shifted the focus of students and faculty onto jobs. Finally, in 1972, BC elected its first socialist government, which took further steam out of the necessarily left-oriented agitation.

The NDP turned out to be even more enthusiastic in support of the colleges than the Socreds had been. In 1973, Dave Barrett’s government agreed to assume 100% of capital funding for the colleges. Speckeen started to see the college through its biggest period of growth in both student enrolment and physical plant, a growth that included the establishment of regional campuses in Vanderhoof, Burns Lake, and Mackenzie.

Speckeen obviously enjoyed talking about how, in 1970, he orchestrated the move of the university transfer faculty and facility (the trailer) across the bypass (which, as he pointed out in his talk, really was a bypass then) to the vocational school. This move was part of “the meld,” the amalgamation of the college with the vocational school. The school had an enrolment of about 250 students, who joined with the now 400 students in the university transfer and technical programs.

The move out of PGSS was a relief to all. While the high-school and college faculties merged well in the teachers’ lounge, and plenty of useful talk was exchanged about teaching (college faculty by and large had little actual teaching experience and no formal training), and while the college brought some excitement to school life (poetry readings, guest lectures, theatre productions and protest marches), there were some conflicts in the classrooms. Speckeen talked about mediating the concerns of one high-school teacher who had left some instructions on the blackboard of his classroom, with “PLO” written beneath them. When he arrived the next morning, all his instructions were erased except for the “PLO.” Presumably, the college instructor needed the board space.

The CNC trailer was moved to a spot near the southernmost vocational building (the Vanderhoof Building) and became the Quesnel Building. Classes started on the new site in September 1971, though some UT faculty were still teaching and staging events at PGSS. About this process, too, Speckeen told some informative and funny stories. One was about how faculty and staff literally carried the equipment, files, office furniture etc. across the bypass. The council hadn’t thought of how the move would actually be funded. Speckeen by that time had learned some wisdom from Moffat, who told him, “Do what you have to do, then ask for permission.”

The meld also included the establishment of a single administration and a single contract for all faculty. Speckeen talked about negotiating the contract, which mostly involved calming the concerns of the vocational-school instructors, who had their own professional association, contract, and pay-scale and were happy with it. Basically, Speckeen was able to give all the vocational instructors a slight raise, and found it amazing how receptive that made them.

Speckeen, who’d worked in the trades through high school, and thought of going on to become an electrician, understood vocational teaching: the curriculum, the teaching infrastructure, the certification process, and the process by which the government bureaucracy (“Manpower”) set quotas for various trades, and funded the instruction. He was a good person to orchestrate the meld.

In late 1972, more portable buildings were assembled near the Quesnel Building. They became the Smithers Building, which incorporated classrooms, offices, and the college library. The College also rented space in a warehouse across 17th, formerly the home of a factory that made kitchen-cupboard doors. A small theatre was built there, by faculty, and there was space for Fine Arts studios and Barry McKinnon’s print shop, the equipment donated by Ben Ginter, the town’s notorious millionaire contractor and brewer, who was always, Speckeen noted, incredibly generous to CNC.

Speckeen praised the contributions of founding faculty to the college and community, mentioning many faculty and staff by name. Gary Bauslaugh, a chemistry instructor and Dean of Arts and Sciences, was instrumental in equipping and setting up the labs. Allistair McVey (Geography) and Ian Johnston (English) staged plays. McVey later got the idea for a college crest and motto. McKinnon staged some impressive readings, one of them in Vanier Hall featuring Al Purdy and attracting an audience of 500 — most of whom had actually come to see a folksinger whose flight had been grounded in Ft. St. John. McKinnon’s print room produced, besides magazines of student poetry and fiction and the faculty newsletter, the Regional District plan for Cottonwood Park and the Caledonia Rambler’s local hiking guide, co-written by Dave King (at the Forest Service) and faculty member Bob Nelson (who was also working with shop instructors to build an observatory).

Gary Bauslaugh

Speckeen seemed especially proud of the outreach programs, including Log-House Construction, assorted shop courses for ranchers etc, and (he was so enthusiastic that I assume he must have taken this course himself) bee-keeping. He told how the college purchased four city lots at auction for construction of Alan Mackie’s log homes — the homes to be auctioned off to fund the program. It turned out that Speckeen and the council were over-enthusiastic. Only one lot was needed, but the city gracefully took the others back.

Dwayne Rubadeau (Psychology) and Bruce Strachan (staff) were singled out for their performances on banjo and piano respectively at Shakey’s Pizza. Speckeen intimated that they were by far the most popular music act in Prince George in the mid-seventies. He praised Strachan for his involvement in community and then provincial politics, and noted that Paul Ramsay, hired into the English department during Speckeen’s regime, went a similar route.

In 1974, Speckeen was notified that the government was prepared to spend some ten million dollars to build and equip a major facility on campus. Planning started immediately, on a sort of extension of the Vanderhoof Building, with local architect Des Parker.

That same year, the Faculty Association was asked to unionize. The NDP wanted it to operate under the Labour Act rather than the Societies Act. Formerly, faculty individually signed a common contract, and disputes were settled collegially. Now, the union would sign the contract, and disputes would be settled by arbitration. Speckeen said nothing about how this worked out for him, but I became involved in the union shortly after I arrived, in 1972, and remember him to be easy to talk to even in the formalized setting of union-employer negotiation.

Speckeen ran into a problem in 1975, when both he and his Student Services director went off for sabbatical leave. This seemed to have been as big a shock to the community as Franke’s equanimity in the face of student protests. To faculty, whose contract included sabbaticals for research, publication, and professional training, Speckeen’s sabbatical was routine, and his replacement at the helm, Gordon Ingalls (who taught philosophy and sat on assorted committees), had everyone’s confidence. Ralph Maida took on Student Services. Both Ingalls and Maida carried out their responsibilities efficiently, and went on, as faculty and in various administrative capacities, to work at CNC until retirement.

Speckeen didn’t discuss any of this. Probably the memory is still painful, as the issue went province-wide, with editorials by Jack Webster and television crews chasing him down at Simon Fraser University where he was taking some introductory law courses.

After the noise died down, Speckeen went on to spend another three years building the college. When he resigned effective December 31, 1978, college enrolment was 3,000 and the new gymnasium (the Fort St. James Building) was in use. The Vanderhoof extension, the main college building, opened in October. It housed a permanent library (on the second floor), a Food Services facility (a cafeteria and teaching kitchen), and more labs and classrooms. The building was designed to be extended upwards — for a time there was an empty (roughed out) third floor, that faculty and staff used for jogging.

The reasons for Speckeen’s resignation are still a subject of speculation. The reasons given, completion of the meld, completion of the building program etc, are suspect. Why wouldn’t Speckeen go on to lead CNC to other successes? Some thought the issue of his sabbatical was still irritating council. Some thought he was considered too focused on University Transfer — the new council (by then a board) was more interested in Technical-Vocational, and appointed its new Principal accordingly.

Whatever the reason for his resignation, by the time the next decade was over, which coincided with the beginning of the end of the new Principal’s tenure, Speckeen’s time at the helm had come to be regarded by the faculty and staff of CNC as a golden age. Speckeen seemed to feel the same way about it in the context of his career.