The Birth of a Satirist

Unlike painters, lyric poets don’t do self-portraits. That would be redundant. But they do sometimes create alter-egos: Pound’s Mauberley, Olson’s Maximus and Berryman’s Poor Henry. Talking about yourself, in the third person, may have something to do with getting outside of the (Wordsworthian) repetition of settings, personal circumstances and attitudes, allowing for more objectivity.

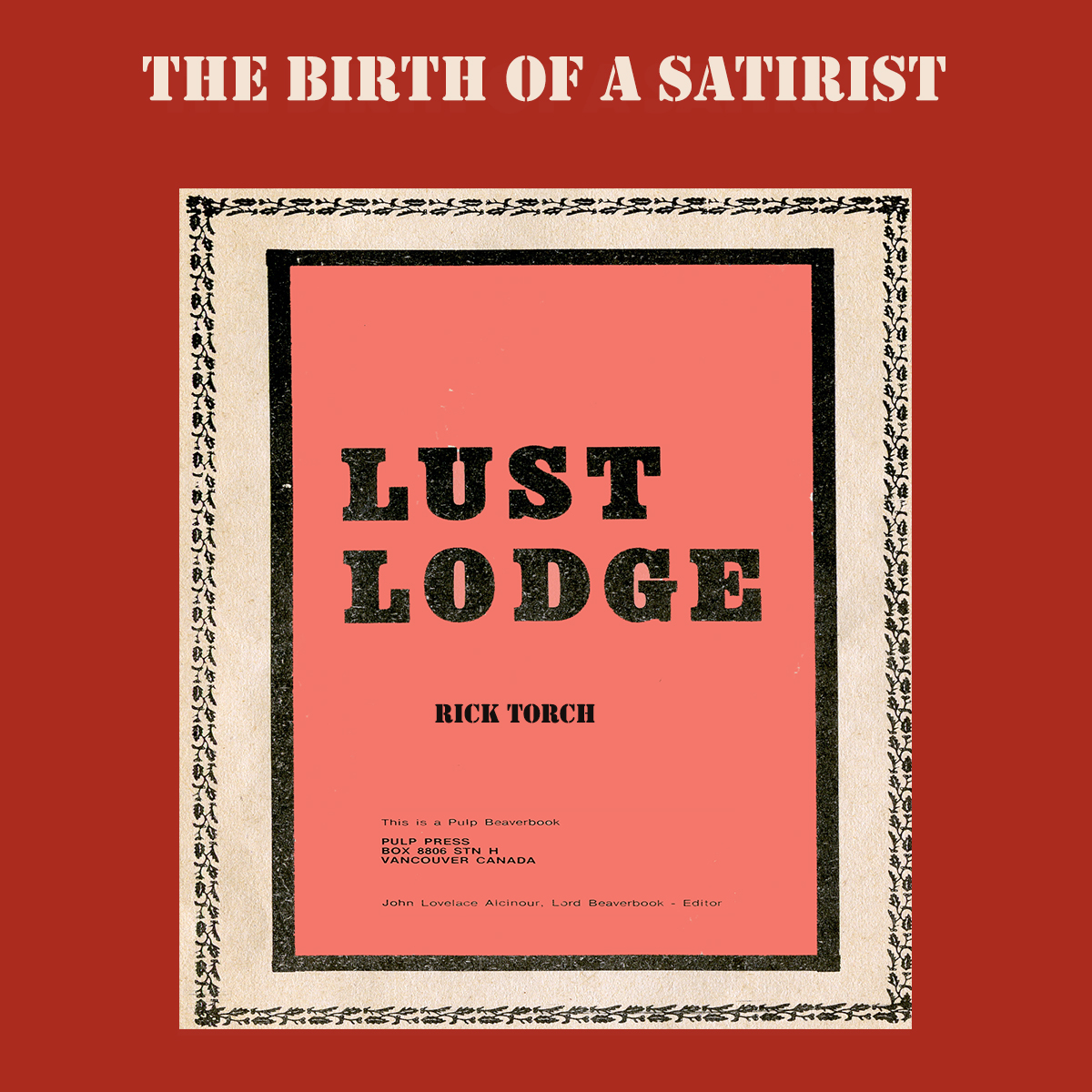

Barry McKinnon has at least three alter-egos that I know of. First (in chronological order of appearance in McKinnon’s oeuvre), there’s Rick Torch, writer of the pornographic novel Lust Lodge, first published in 1973 in a “college edition” with study notes. Second, there’s Jack the Organizer of the 1979 poem of the same name — a poem published in McKinnon’s The the, (Coach House Press, 1980). Third, there’s Jack Daw, a poet and critic who, like Shakespeare, sometimes adds an “e” to the end of his name. Daw’s Selected Poetry, a slim, undated chapbook, was published by the untraceable Under / Ground Press of Berkeley, California, funded by the similarly untraceable Young Canadian Writers Fund, and touted by untraceable back-cover blurbs from four prominent Canadian magazines. Daw’s prose remains unpublished.

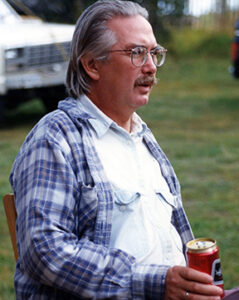

Jack the Organizer is explicitly connected to McKinnon. He is the hero of a lyrical-dramatic poem, written from overlaid first, second and third person perspectives. Rick Torch’s connection was for a time less obvious. He looks like McKinnon; there’s a grainy photo of him in back of Lust Lodge, and the photo is credited to Joy McKinnon. But McKinnon stopped winking from behind Torch’s and his own wife’s backs when he published Lust Lodge under his own name in a collection of local short stories and poems, The Pulp Mill (1977). Jack Daw’s poems and prose were circulated by McKinnon himself, and Daw’s biography, evident in the writings themselves and recounted by Daw’s (genetically connected?) editor Richard Daw, parallels McKinnon’s in many ways. But Jack Daw’s connection was never made explicit.

Lust Lodge is a satire. The plots and euphemistic language of pornography are exaggerated to the point of nonsense. The plot features a frame story, in the course of which the character Marvin, in a porn store, covertly rips the plastic-bag covering off Lust Lodge. On page 82, he reads about Barbara and Tad, who are having sex in a ski lodge while Tim, presumably Barbara’s ex-whatever, is outside collecting evidence (for lawyers, it seems) with a polaroid camera. Tim gets the shot he wants: “Barbara’s erect nipples, her face graphically expressing a crescendo of pleasure, the centre of her desire exposed to full view.” As Marvin is reading this, the most beautiful woman he has ever seen appears to his right, moving towards the $5.00 sadomasochism stand. Marvin is aroused, but freaked out. “Was she a plastic bag spy for the manager?” And so it goes, ending when Marvin, struggling to get Lust Lodge back into its bag, feels a strange hand on his shoulder.

There follows a student guide to the novel, and a student guide to Marvin, with questions like “How did Tim learn to work the cold clip in such inclement weather,” and “why did D. H. Lawrence have nothing to do with this?” Finally, the editor’s notes announce, among other things, that “Mr Torch . . . has quit writing (even for pleasure).”

Jack the Organizer serves as a key to interpreting the satires attached to that other Jack, Jack Daw. The first Jack embodies the existential dilemma that activates all of McKinnon’s poetry: we live in our minds and also in civil society. Or, to put it another way, we feel ourselves to be individuals, but have to act as lovers, parents, employees, citizens — as members of a group. The title of the book that “Jack the Organizer,” appeared in, and of the section of that book that includes it, is taken from Wallace Stevens, who used the phrase to designate that which the lyric poet, described as “the man on the dump,” wants to “get near” — which is “oneself” and also “the truth,” or “The the.”

Jack is “a kind of poet,” and is functioning as a kind of citizen — in this case an official or politician, chosen by his group to be in charge of some sort of winter-fest or service-club party. McKinnon too was an organizer — of what was, from 1969 to the early 1980s, one of the most active Canada-Council-funded reading and visiting-writer programs in Canada. The program included a publishing aspect, whereby each writer received a broadside or chapbook printing of the poems read, some of these publications hand-set by McKinnon and students and printed on high-quality paper. McKinnon’s hand-set publications are attractive: in 1981 he won the Malahat Review award for excellence in letterpress and broadside design.

Like McKinnon, Jack, in order to do his job, has to be, and evidently is, less drunk than anyone. This is because he has to provide the “paper plates” and the “trophies,” choose the winners of the beauty and other contests, “stack those chairs” and “clean up,” and “see the last drunk home.” But like all poets and politicians, he’s out of his element and, unlike some, humble enough to know it. He’s a bit of a fraud, in his “elevator shoes.” He is operating above his pay-grade. His responsibilities are beyond his abilities. He has trouble with the mike and some of the drunker men who “grab these mikes — carry off the queen or ladies in waiting, or / last year’s queen — or anyone.”

Similarly, “poetry won’t allow all to be told” — is not adequate to depicting our dilemma, answering our questions, helping us in our civic roles. This causes conflict and anxiety in poets:

jack doesn’t know his own mind and is therefore a kind of

poet. He knows the unbearable pressures and is therefore, also

human . . . .

In the course of the poem, McKinnon becomes Jack, slipping into him through two incomplete parenthetical insertions in the first stanza. Accordingly, throughout the poem, McKinnon describes Jack in the third person; he addresses, gives him instructions (“kiss the music Jack”), and asks him questions (“is your finger on the nike zeus”) in the second person; and he has him speak directly in the first person. Grammatically, some lines could be Jack’s, some McKinnon’s:

I am as

sad as I can be — think of our 15 billion years — how any

tribe must dance and choose their queen — the eternal

goddess (in this case dressed in red pump shoes,

a corsage. kiss her Jack

Jack and McKinnon “can’t really do anything but / be responsible.” The upside is that they accept responsibility, and do their best, freeing the rest of us to enjoy the party. We vote politicians into office to do what we know they can’t do — which is, mostly, make us get along, or protect us from one another. When they fail, or sometimes even when they succeed, we vote them out, vote in someone else, and go off to watch the game. We are conscious, of course, of the dangers — the “Nike Zeus” represents a whole kit of governmental tools over which we have given politicians control.

Similarly, we read poetry without expectation of applicable answers. Any such answers have to involve changes in us and our civic polities, changes that poets — as well as politicians, philosophers, scientists, artists, martyrs and messiahs — have provided glimpses of, but that we know we can’t entirely grasp or face. The message we do glimpse is really quite simple. As W. H. Auden put it, “we must love one another or die.” Being what we are, however, we can’t love one another or count on anyone to love us. People who can do it end up crucified. All we can hope for is someone to care:

who will

care. You will, Jack

it’s hard

to be humble when you’re great. in my own way I love

you all. This must be my real purpose

you’re nothing Jack in your

elevator shoes they chose you for no reason. but

they knew you could do it.

Jack, illustrating the human dilemma, the discrepancy between ideality and reality, is a comic character. He could be a tragic one, as Marvin maybe ended up being, but in the end Jack’s party is a success. He did it. And McKinnon, in all his poems, sees himself as comic. To presume to write poetry is to appear in elevator shoes. McKinnon’s act, schtick or, as Leonard Cohen put it, “con” — his way of dealing with the existentialist dilemma — is that of the morose, depressed, cynical, but stubborn and caring loser.

McKinnon appears in his poems as an urban Dagwood, often listing consumer items (stuff that ends up on the dump) and their cost: “if the popcorn is 50 cents / buy it.” He calls this feature of his poetry “Woolcoco,” after the chain department store. He is the college instructor with a migraine, consigned to “The Centre” to teach “developmental studies,” puzzling with students over “the rule for ‘more better’.” He is (quite often) the guy at the table (or in the band — McKinnon is a talented drummer) in the hotel bar, watching the cowboy with muddy boots jump onto the pool table to replace the light bulb, watching the “midget singer with the afro hair,” watching the guys watching the stripper. He is the stressed but patient father taking his whining daughter to the Nanaimo bathtub races and trying to get her out of there fast when what was supposed to be “fun” turns violent, and storefront windows are being smashed and parked cars rolled by drunks. He is the inadequate husband thinking of “sex at 31.” He is the man in late middle age contemplating the diagnosis of “arrhythmia.” He is the poet whose style features a rhetoric of uncertainty, of tentativeness — constant grammatical enjambment and titles like “The the: fragments,” “I Wanted to Say Something,” “An Unfinished Theology,” “It Can’t Be Said,” “Thoughts / Sketches.”

But the loser, the bumbling organizer, the inadequate husband and father, the human being conscious of his mortality, the poet on the dump looking for “The the,” is also a sort of messiah, a heroic figure. Despite the act, despite the fatalism, hesitation and insecurity, McKinnon’s message is clear: I care. I am the one responsible for trying to make things work.

McKinnon is wary about his pronouncements, and encourages us to be wary — of grammatically impeccable statements, of easy eurekas, of pronouncements that turn out to be sonorous but ambiguous, of people (managers, politicians, other poets) who seem to “know the stakes.” He shows us how to familiarize ourselves in detail with the contents of the dump before engaging in poetic sublimation — before muttering, as Stevens has it, “aptest eve” over “the mattresses of the dead,” or “Invisible priest,” when listening to “the blatter of grackles”. He has learned how to avoid, in his poetry and thus in life, any illusions generated by the tendency to withdraw into the self:

I am in a desert

of snow, each way

to go presents an equal

choice, since the directions, &

what the eye sees is the same

if there were some sticks, you would

stay & build a house, or

a tree would give a place to climb

for perspective. if you had a match, when

the wind didn’t blow, you

would burn the tree for warmth, if

the wind didn’t blow & you had a match

there is this situation where love

would mean nothing. the sky is

possibly beautiful, yet the speculation

is impossible, & if you could sing, the song

is all that would go

anywhere (“Bushed,” The the)

Around the time McKinnon released Jack the Organizer on the world, Jack Daw began to appear. The second Jack is not caring, but angry. Nor is he a “sort of” poet, but a real, if unsuccessful (in his own mind) and embittered one. As his editor, Richard Daw, describes Jack’s life, in a tentative introduction to a proposed collected works, the details line up roughly with McKinnon’s own biography: born in Calgary, taught creative writing (though on sessional, short-term contracts), brought Margaret Atwood and Al Purdy in to read and talk to students, got Canada Council writing grants (two, just like McKinnon), loved his students but hated his job, was attacked by administrators and the parents of his students for writing, publishing and teaching obscene poetry and prose, and was “canceled” by assorted university administrators and professors for not using gender-neutral pronouns, for hurtfully describing strippers and midgets in a bar, for coming from a “settler” family of wheat farmers, and for being a member of the patriarchy.

Obviously, readers have to have some knowledge of the literary-academic scene to appreciate Daw. Only poets read poetry, so his audience is naturally limited, and few would recognize the poets being parodied. The poems, however, are funny in themselves because of the overblown metaphors, stumbling enjambments, swear-words and portentous wisdom. Daw introduces his poems as being revolutionary, part of “a war for the imagination.” He also acknowledges that this claim is pretentious. Revolutionaries usually have an idea of what they want. Daw doesn’t. At the end of his fiery introduction, he adds, “Mostly I like to drink.”

The revolution that Daw alludes to seems to be a mere protest against that main antagonist to artistic freedom at the time, the Moral Majority, which objected mainly to four-letter words, to allusions to drugs and excessive drinking, and to graphic descriptions of violence and sex. Daw’s poems are full of such allusions. Daw’s prose, on the other hand, while it still insists on prodding the Moral Majority, takes on the next generation of morality police, the academic post-structuralists — the postmodernists, the postcolonialists, and the woke.

Daw’s move from poetry to prose took place at a crisis in McKinnon’s teaching career. He’d always gotten complaints from parents, local newspaper editorialists and radio commentators, and college administrators for some of the content of the readings he organized, and for the teaching and publishing of pieces like Brian Fawcett’s story “Walking Cunt” and his own Lust Lodge. McKinnon has described this in some detail in his chronicle of the Caledonia Writing Series — the name of his publishing project that was housed by the college and funded by the Canada Council. The 40-page chronicle appeared in Simon Fraser University’s Line magazine (1983).

College administrators were supportive at first, as McKinnon says, but his February 1980 Words / Loves Conference, featuring American poet Robert Creeley and a dozen or so prominent Canadian poets and fiction writers, resulted in a flurry of parental and media complaints. The college administrators, arguing that the college plan now mandated a move away from the University Transfer program into polytechnic education, closed down the print shop that McKinnon had built up (a platin press and some offset equipment) and piled the equipment outdoors in a compound in the vocational area. Then they cancelled Creative Writing, the course McKinnon was specifically hired to teach. Finally, in 1983, McKinnon was laid off, and assigned to teach remedial English through what was to be his last semester.

This was a transitional period for Daw, after which he appears in full force. Here’s a prose parody from that time. It makes fun of self-study “modules” used in remedial training. It has my name, instead of Daw’s, on it because I originated the “asshole” module that was, for a time, actually used. McKinnon gave it its satiric edge, adding details that echo the student guide to Lust Lodge. McKinnon liked the “Dr.” in front of my name, I think because it emphasizes the discrepancy between the formality of my title and the zaniness of “my” content:

Metaphor

by Dr. John Harris

Trevor is an asshole!

The word “asshole” in this sentence creates a metaphor. Trevor is not literally an asshole, though he has an asshole. Trevor (human), asshole (body part). Asshole and “ass” are also colloquial slang words for various euphemisms like anus, bottom end, gluteus maximus, tush, etc. Can you think of more such euphemisms?

To understand “colloquial”, “slang”, and “euphemism” usages, see Module 13.

Metaphor uses the comparison of one thing to another. Unlike simile (see Module 15) that formalizes the comparison with “like” or “as,” metaphor directly fuses the two parts of the comparison. They join to make new meaning. Trevor is an asshole!

If Trevor is an asshole, what other words/metaphors to describe him come to mind? Make your own metaphors! Choose one of the following: jerk-off, fuck-face, bozo, shithead, college administrator, remedial English teacher.

In a short paragraph, describe an asshole you have known.

McKinnon was re-instated in his job because of a massive letter-writing campaign orchestrated by writer-friends Pierre Coupey and Brian Fawcett. About 80 established Canadian writers participated, including Margaret Atwood, Al Purdy, Michael Ondaatje, and the Vancouver Tish poets: Frank Davey, Fred Wah, and George Bowering. Creative writing came back with McKinnon, but he never again taught it, turning it over to a junior member of the department. He taught only workshop composition courses — professional, technical and business writing. He purchased a platen press and other equipment and moved it into his basement, a process described in Line. Gorse St. Press replaced the Caledonia Writing Series.

The first books and articles describing and applying post-structuralist theory came out of the Canadian English department shortly after McKinnon started his career in 1969. They were written by the Tish poets, who were the first wave of “deconstructionist” poets in Canada. Davey, as a prominent academic theorist / critic, and then the head of Department at York and chair of the Association of College and University Teachers of English (ACUTE), was the first in Canada to use the word “postmodern,” and to battle the old humanistic or thematic approach to English teaching and to departmental literary criticism. By the 1980s, just about every university English professor was obsessed with what they called “theory,” and the previous theory, humanism, was in retreat. Deconstructing, or sniffing out sexism, racism, weightism, etc in the traditional “canon” of English Literature, enforcing political correctness, and pursuing identity politics and “social justice” themes, became the business of the department. The department also continued the affirmative action policies that it had started under the influence of feminism, generating in its staff, and in the editorial staff and contents of its periodicals, the zoo-like feature of multi-species representation.

The main enforcer of poststructuralism in Daw’s life is Dr. J. wAyne Bundy. His name is a compilation of the names of a serial killer and an actor in cowboy movies, and is formatted in a pretentious way (T.S. Eliot’s J. Alfred Prufrock). The upper-case A in “wAyne” is an allusion to post-structuralist objections to the sexism, racism, and (male) linearity that is, according to theorists, “systemic” in English. Moving the upper-case letter over to the second letter in a name is an “act of resistance” intended to “subvert” the “hegemonic” rules of English grammar, spelling and punctuation. In the course of Daw’s satires, Bundy plays various roles. Usually, he is a senior member of a department in which Daw was a junior member. Sometimes he is a professor at a university adjacent to Daw’s college. Always he is more powerful than Daw.

In “The End of the World,” Daw tells the story of the time that a young Donald Trump took one of Bundy’s creative writing classes. The Donald produces an essay about nuclear annihilation:

ok, it’s gonna be really really great, a beautiful thing, you’ll love it . . . the biggest cloud in the world . . . . and it’ll be great because I’ll tell you what, there will be no more deals, I mean it, with china, canada, mexico . . . . we’ll grab those fags by the pussy, and it’ll be great . . . you’ll love it, really really love it.

Dr. Bundy gives Trump a C+, and his commentary is a mix of objectivity, irony, condescension and obsequiousness:

Try to follow my instructions for a 500-word story. You’re about 300 short on this one . . . . What a really, really, really great title. . . . You might want to think of the ambiguity (double meanings) of the words ‘pussy’ and ‘fag’ . . . . If you’re interested, I also freelance (not really free, ha, ha) . . . and I think that, after a few hours with me (the fee can be mutually arranged) we can really forge (shape) the story and get it to an A+ level and with my help and contacts find a journal to accept this very germane (important) piece of writing. See my attached resume and qualifications. Again, really, really, really great to have you in class.

Because this satire involves a character familiar to everyone, and a view of teacher-student engagement familiar to those who’ve taken or taught English or creative writing, “The End of the World” is the most generally accessible of Daw’s satires.

McKinnon taught English and technical writing right through the postcolonialist toppling of statues of Canadian politicians, the Black Lives Matter and Me-Too protests, the firing of, or cancelling of events on campuses featuring, publicly-known figures like Henry Kissinger and Jordan Peterson, and the witch-hunts of politically-incorrect students (Lindsay Shepherd) and faculty (Steven Galloway). These events resonated through academic institutions in Canada. McKinnon was also aware of events that were closer to him. In 2018 he was alerted by his old friend Sid Marty of the firing of Jeramy Dodds, editor at Coach House, publisher of The the. Dodd’s “crime” was an accusation from a former girlfriend, later withdrawn, of harassment. McKinnon knew of John Metcalf, accused of racism for his negative criticism of a book by M. G. Vassanji. Unfortunately for the accusers, Metcalf happened to be the adoptive father of two Indian children, but that didn’t matter; he was driven out of Humber college. And George Bowering, a close friend of McKinnon’s, was “cancelled” by the promotional staff of ECW Press because they thought his book No One (2018) was misogynistic.

By keeping his head down, McKinnon’s relationship with parents, administration, and local media improved. And his Gorse Street Press didn’t attract local public attention, not even when it won awards for design and writing. But his earlier books started to draw the attention of Bundyist enforcers. In 1988, Pauline Butling, a professor at the University of Calgary, attacked McKinnon’s Poets and Print, a Line-magazine series of interviews with BC poet-publishers. She accused him of attempting to “erase women’s achievements from the historical record.” In 2008 McKinnon (now four years retired from his job), was attacked by Derek Beaulieu, of the same university, for I Wanted to Say Something (1971, 1985). That book, in describing the Alberta prairie as “the lovely new land where we now stand,” and telling the story of McKinnon’s grandparents at the turn of the 20th century starting a wheat farm south of Calgary, was, according to Beaulieu, voicing “an ideological support for economic growth and expansion, and a reiteration of dependence on oil and gas resources.” Contemporary Alberta poets, Beaulieu says, are unwilling to, like McKinnon, “trace / the lineage, to claim . . . innocence” or to “inherit the earth from their journey,” and to fall for the “Modernist urge to construct either structure or meaning.”

More of this weirdness came McKinnon’s way in the course of the “Prince George poetry war” — the name attached in 2012 by Brian Fawcett to some altercations between creative writing at UNBC and the program at the college. Fawcett interpreted it as an engagement in a larger war between the poetics of Robert Creeley, Charles Olson, and the New American Poetry which led, through Tish, to the war between postmodernism and liberal-humanism. The poet Greg Lainsbury took it as a turf war between UNBC and CNC over who owned local poetry. McKinnon stayed loyal to the program he’d founded, not deflected by the honorary degree that UNBC bestowed on him in 2006.

Around 2008, UNBC acquired the support of Ken Belford, an old friend of McKinnon’s who is present with him in Al Purdy’s Storm Warning anthology, and Margaret Atwood’s New Oxford Book of Canadian Verse. Belford had done many readings for McKinnon, starting in 1970. He was a good reader, and popular with students for his local settings and characters. McKinnon had published Belford’s Sign Language and Holding Land through Gorse Press, in 1979 and 1981 respectively, and had assisted in editing Pathways into the Mountains (Caitlin Press, 2000). McKinnon was upset by Belford’s cutting off of their friendship and his accusations of sexism, racism and negligence regarding environmental issues.

As that was happening, McKinnon faced a number of minor irritations. First, a student announced on a UNBC blog that she couldn’t bring herself to submit her chapbook to the Seventh Annual Barry McKinnon Chapbook Award contest because the instructor at CNC who ran the contest “promotes violence against women.” This reflected on McKinnon’s sponsorship of the contest. The student was forced to take the blog down when the CNC instructor objected, but funding for the “McKinnon Chapbook Award” was pulled (due to “budget priorities”) by UNBC shortly after. In 2012 a student, originally from the college, was barred from UNBC’s senior creative-writing course. The professor explained, “I know it may not seem fair, that I am painting you with a large CNC brush, but . . . ‘battle lines’ have been drawn (not by me). I feel that I have to protect myself.”

The Bluah Gaskett File, introduced by Richard Dawe, presents documents collected by Jack that tell the story of a “poetry war” struggle — a struggle, occurring at The College of Athena by the Sea (COABTS), that actually goes bad for Bundy. Bundy had alerted students and administration to Dawe’s use of “inappropriate vocabulary” in his early poems. “These were the words and phrases someone redlined as harmful: ‘Indians’, ‘chicks’, ‘jerked off,’ ‘fuck to all that’, ‘eat shit’, ‘milky breasts in moonlight’ etc. etc.” Dawe was laid off. As an act of revenge, Jack acquires incriminating documents from a drinking buddy who runs the college shredder.

The documents concern the “Bluah Gassket” poetry contest, judged by Dr. Bundy. This contest “calls for poems that connect with Gaskett’s core values by advancing or aligning with social justice, anti-racist, anti-sexist, anti-capitalist, and / or ecofeminist thought.” Bluah Gassket was a founding member of the (COABTS) English department, who achieved, possibly due to a number of “cerebral accidents” in his youth on a farm, some status, within English departments, as a poet. These cerebral accidents result in his writing of “sermonic . . . revelations of profound ills in modern society: “racism, unicorn sex, chrono-capitalist exploitation, nontransgenderism, cubism, neononcolonialism, autohomophobia, onanism, and all other social islamic oppressions.” Gassket also suffers from bouts of rage, “especially at poetry readings where other poets came to ‘steal’ his ideas.”

The first submission that Bundy receives is from one Darryl Stagness, who claims a special bond with Gassket because he suffers from the same mental problems and has a similar knowledge of nature:

I am also a fledgling poet, harmed during childbirth and because of the pills they always give me. Harmed like Gassket, I was a guide for sport fishermen and big game hunters in Vermont. I know about the forest, its’ flora and fauna (birds and bees). You only have to look at all the trees cut down to see the harm to nature and it’s true peoples. Also I agree with Gassket that German hunters should not be guided. Hes’ absolutely right about the nedos (white men!) and poet white boy gangs who exploit, steal, and cause allot of harm also to me. I hope with these thoughts that you will consider my poems for the first prize. Its inspired by Mr. Gasskets’s verse and his life and all of the things you say in your ad. Thank you for any considerations. Also I’m sorry for this long letter. They give us a lot of paper after lunch to record our thoughts that are good for the meetings later in the day. I should also note that my counsellor who also helped me with this letter, has registered me in your poetry writing class for this fall.

Anyway, here’s a list of the poems for you to consider sent in another envelope. Please also, don’t loose them because I don’t have other copies. My best one is with this letter below called yippppyee kii o ki yaaaay plus the ones in another envelope such as,

the redbarrel

the king of ice cream

Gloucester to maximus out

canto xv11

stopping by trees while it was raining one night the waisted land

Thanks again Professor dr.Bundy. See you on prize podium!

Unfortunately for Bundy, he angrily rejects the poems, accusing Stagness of plagiarism:

Robert Frost wrote “stopping by woods on a snowy evening.” Do you fucking well think that “stopping in rain” is going to throw me off the trail? or “waisted” instead of “waste” will hide you from your theft of T.S. Eliot’s great poem?

Quite frankly, I think you are a fucking idiot driven by a sense of greed to win $1000.00. The more I think of this the more I get pissed right fucking off. I will do all in my power to keep you from my class despite our open door policy for mental patients and people with special learning needs, like you! Its’ obvious you are severely harmed and possibly dangerous. I would also suggest to your counsellor that writing is not good therapy for you. In fact, it might contribute to your condition as a psychopathic pathetic nut case.

Stagness is traumatized, but not to the extent that he fails to get a lawyer. The Dean of Humanities — Dr. Ron(a) Harlow — contacts Bundy:

Dr. Bundy, I just had another call from a Daryl Stagness and his lawyer and counsellor. Please see me immediately re. our suggestion that you take an immediate extended health leave and consider an offer for early retirement or a severe tenure and salary reduction before this matter goes to the board chairman.

Bundy pleads pressures of work, connected particularly with judging the hundreds of submissions to the Gaskett contest. Harlow replies:

Can you prove to me or any judicial committee that the poems of Mr. or mss. stagness are actually copied out of some anthology? Is it not a common practice for writers to (“steal” is not quite the word) but “borrow” from others? And as you know, the rules for plagiarism have changed in the last few years because of the internet and cultural customs that don’t consider plagiarism as academic theft. To whit: our Chinese students do not have a tradition like ours. We must take these cultural significances into consideration in order to keep our foreign applicants interested in this institution, (especially those who have trouble with reading and writing English and want into our medical and dental school). We need to give an inch on these outdated matters and academic requirements. Apparently, you have not.

Bundy attends an anger management class recommended by Harlow and drafts a letter to Stagness that begins:

Yo, daryll, how’s it going dude? I just want to say I got a little carried away in my letter to you. I was under a lot of stress and kind of blew it because of workload and the medications I need to take. Some days I go a little strange and don’t know up from down. Now I think I do! Those poems I was so harsh on are actually pretty good (and show that you’ve done your homework by reading frost, Olson, Stevens pound and Eliot. What an impressive list of mentors you’ve chosen! My dean and I have discussed the difference between borrowing and stealing, and I assure you that I won’t make the same mistake again. I guess we’re all in school to learn our lessons aren’t we?

On it goes, one memo, letter or formal announcements after another, all rescued from the shredder. Harlow hears (via Dawe) about Bundy slagging him in the faculty lounge as a “fat bald motherfucker.” Bundy launches a harassment lawsuit against Harlow, Dawe, Stagness . . . and the guy who runs the shredder. It ends with the president of COABTH cancelling creative writing entirely.

There’s no doubt that McKinnon was angered by his long struggle with the censorious forces of the Moral Majority and postcolonialism. That struggle is likely to continue. But this is all to the good, especially for us, because McKinnon has learned to express his anger in satire. He seems likely to continue with the satirist’s work — to point out our foibles so that we might correct them, to make us take ourselves less seriously, and to allow us to enjoy some salubrious laughs as we pick our way through the dump.